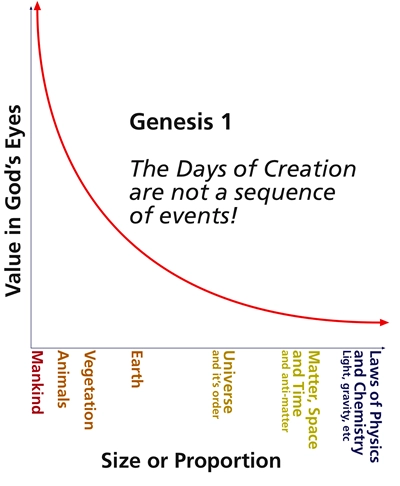

When we read Genesis 1, it’s easy to assume the “days” of creation describe a literal sequence of 24-hour periods, detailing how God brought the world into being. But what if the chapter isn’t about chronology at all? What if it’s a theological framework revealing God’s character and the value He places on His creation? I propose that Genesis 1 is best understood as a graph, with one axis representing size (from the vast universe to individual humans) and the other showing value in God’s eyes (culminating in humanity as the pinnacle). Let’s explore this idea, looking at the Hebrew word for “day,” the sequential language of Genesis 2, and how English metaphors for “day” support a figurative reading.

Genesis 1: A Graph of Size and Value

Instead of a timeline, I see Genesis 1 as a graph plotting two axes: size and value in God’s eyes. On the size axis, we move from the cosmic scale—light, the universe, laws of physics, and the earth (days 1–3)—to the smaller and more specific: plants, animals, and finally humans (days 4–6). On the value axis, the worth in God’s eyes increases as the size decreases, with humanity, made in God’s image (Gen 1:26–27), as the climax. One human is worth more in God’s eyes than all the rest of creation combined.

The structure of Genesis 1 supports this. The “days” aren’t necessarily sequential events but thematic categories, showing God’s orderly progression from the grand to the particular, from lesser to greater value. The Sabbath (day 7) caps this framework, highlighting God’s desire for relationship, which humans uniquely share with Him. My graph below illustrates this:

The days of creation are not a sequence of events. Instead, they reveal God’s character—His order, purpose, and prioritization of humanity.

The Hebrew Word Yom: Literal or Figurative?

The Hebrew word translated as “day” in Genesis 1 is יום (yom). This word is versatile, meaning a literal 24-hour day in some contexts but also an indefinite period or significant time in others. For example, in Genesis 2:4, yom refers to the entire creation period: “in the day that the Lord God made the earth and the heavens.” Clearly, yom can be figurative, much like how we use “day” in English metaphors (more on that later).

In Genesis 1, the structure—“evening and morning,” ordinal numbers (first, second, etc.)—suggests a literal 24-hour day in traditional readings. But the chapter’s poetic style and theological focus allow for a metaphorical interpretation. If the author intended to ensure a literal 24-hour day, they could have used repetitive phrases like יום ליום (yom l’yom, “day by day”) or בכל יום (b’chol yom, “each day”), which emphasize daily cycles elsewhere in the Bible (e.g., Numbers 7:12–83). Alternatively, a more prosaic style, like in Leviticus, could have locked in a strict timeline. But no single Hebrew word is more specific than yom for a literal day, and the author’s choice of yom preserves the text’s flexibility.

Given Genesis 1’s purpose—revealing God’s character and His value of creation, and not the how of creation—this flexibility is a strength. Yom can represent a “phase” or “category” of creation, aligning with the graph’s thematic progression rather than a rigid timeline.

English Metaphors for “Day”

The figurative potential of yom mirrors how we use “day” in English. Consider metaphors (not similes) like “red letter day,” “every dog has its day,” or “the sunset years.” These phrases use “day” to signify a significant time or period, not a literal 24-hour span. A “red letter day” marks a noteworthy event, “every dog has its day” means a time of success, and “the sunset years” refers to old age. Similarly, yom in Genesis 1 can metaphorically denote stages of creation, each highlighting a shift in size and value, not a literal day.

Genesis 2: A Sequential Contrast

Since both chapters can’t be a record of sequence—that would be contradictory—one must choose between Genesis 1 and Genesis 2 to find sequential language. Even though it’s a sparse record, Genesis 2, not Genesis 1, provides the sequence, or at least a small piece of it.

Genesis 2:4–8 "4 These are the generations of the heavens and the earth when they were created, in the day that the LORD God made the earth and the heavens. 5 When no bush of the field was yet in the land and no small plant of the field had yet sprung up—for the LORD God had not caused it to rain on the land, and there was no man to work the ground, 6 and a mist was going up from the land and was watering the whole face of the ground— 7 then the LORD God formed the man of dust from the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living creature. 8 And the LORD God planted a garden in Eden, in the east, and there he put the man whom he had formed."

Genesis 1 is thematic, Genesis 2 shifts to a sequential narrative, focusing on humanity’s creation and role. This chapter uses words that imply a timeline—unlike the diversity of yom.

Words like “generations” (תּוֹלֵדוֹת, toledot, in Gen 2:4, “These are the generations of the heavens and the earth”) signal a chronological narrative. In Genesis, toledot often introduces a sequence of events or descendants, as seen in later genealogies like “These are the generations of Noah” (Gen 6:9) or “These are the generations of the sons of Noah” (Gen 10:1), which trace historical progressions. Here in Genesis 2:4, toledot marks the shift to a more sequential account of creation, focusing on the specific events of humanity’s formation. Other words like “before” (בְּטֶרֶם, b’terem, in Gen 2:5, “before any plant of the field had yet sprung up”); and “then” (implied in the narrative flow, e.g., Gen 2:7, where God forms man and then breathes life into him). This sequential language contrasts with Genesis 1’s structured “days,” reinforcing that Genesis 1 isn’t about chronology. Instead, Genesis 1 uses yom to organize creation into categories of size and value, while Genesis 2 details specific events, grounding humanity’s story in a timeline.

Genesis 2:4 even uses a singular yom to refer to all the ‘days’ of creation in Genesis 1—‘in the day that the Lord God made the earth and the heavens’—clearly indicating that these are not literal or sequential 24-hour periods but a unified creative act viewed as a single ‘time.’

Why This Matters

Reading Genesis 1 as a theological graph rather than a timeline shifts our focus to God’s character. The “days” reveal His order, purpose, and deep value for humanity, culminating in the Sabbath as a sign of relationship. The flexibility of yom, the English metaphorical use of “day,” and the contrast with Genesis 2’s sequential language all support this interpretation. Genesis 1 isn’t about how or when creation happened—it’s about who God is and what He values most: you and me.